No products in the cart.

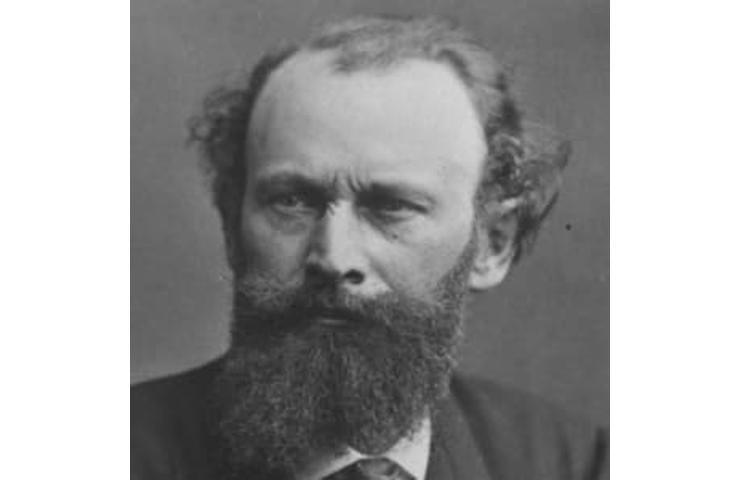

Painter (1832–1883)

Edouard Manet was a French painter who depicted everyday scenes of people and city life. He was a leading artist in the transition from realism to impressionism.

Synopsis

Born into a bourgeoisie household in Paris, France, in 1832, Edouard Manet was fascinated by painting at a young age. His parents disapproved of his interest, but he eventually went to art school and studied the old masters in Europe. Manet’s most famous works include “The Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia.” Manet led the French transition from realism to impressionism. By the time of his death, in 1883, he was a respected revolutionary artist.

Younger Years

Impressionist painter Edouard Manet fell dramatically short in meeting his parents’ expectations. Born in Paris on January 23, 1832, he was the son of Auguste Manet, a high-ranking judge, and Eugénie-Desirée Fournier, the daughter of a diplomat and the goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince. Affluent and well connected, the couple hoped their son would choose a respectable career, preferably law. Edouard refused. He wanted to create art.

Manet’s uncle, Edmond Fournier, supported his early interests and arranged frequent trips for him to the Louvre. His father, ever fearful that his family’s prestige would be tarnished, continued to present Manet with more “appropriate” options. In 1848, Manet boarded a Navy vessel headed for Brazil; his father hoped he might take to a seafaring life. Manet returned in 1849 and promptly failed his naval examinations. He repeatedly failed over the course of a decade, so his parents finally gave in and supported his dream of attending art school.

Early Career

At age 18, Manet began studying under Thomas Couture, learning the basics of drawing and painting. For several years, Manet would steal away to the Louvre and sit for hours copying the works of the old masters. From 1853 to 1856, he traveled through Italy, Germany and Holland to take in the brilliance of several admired painters, notably Frans Hals, Diego Velázquez and Francisco José de Goya.

After six years as a student, Manet finally opened his own studio. His painting “The Absinthe Drinker” is a fine example of his early attempts at realism, the most popular style of that day. Despite his success with realism, Manet began to entertain a looser, more impressionistic style. Using broad brushstrokes, he chose as his subjects everyday people engaged in everyday tasks. His canvases were populated by singers, street people, gypsies and beggars. This unconventional focus combined with a mature knowledge of the old masters startled some and impressed others.

For his painting “Concert in the Tuileries Gardens,” sometimes called “Music in the Tuileries,” Manet set up his easel in the open air and stood for hours while he composed a fashionable crowd of city dwellers. When he showed the painting, some thought it was unfinished, while others understood what he was trying to convey. Perhaps his most famous painting is “The Luncheon on the Grass,” which he completed and exhibited in 1863. The scene of two young men dressed and sitting alongside a female nude alarmed several of the jury members making selections for the annual Paris Salon, the official exhibit hosted by the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Due to its perceived indecency, they refused to show it. Manet was not alone, though, as more than 4,000 paintings were denied entry that year. In response, Napoleon III established the Salon des Refusés to exhibit some of those rejected works, including Manet’s submission.

During this time, Manet married a Dutch woman named Suzanne Leenhoff. She had been Manet’s piano tutor when he was a child, and some believe, for a time, also Manet’s father’s mistress. By the time she and Manet officially married, they had been involved for nearly 10 years and had an infant son named Leon Keoella Leenhoff. The boy posed for his father for the 1861 painting “Boy Carrying a Sword” and as a minor subject in “The Balcony.” Suzanne was the model for several paintings, including “The Reading.”

Mid-Career

Trying once again to gain acceptance into the salon, Manet submitted “Olympia” in 1865. This striking portrait, inspired by Titian’s “Venus of Urbino,” shows a lounging nude beauty who unabashedly stares at her viewers. The salon jury members were not impressed. They deemed it scandalous, as did the general public. Manet’s contemporaries, on the other hand, began to think of him a hero, someone willing to break the mold. In hindsight, he was ringing in a new style and leading the transition from realism to impressionism. Within 42 years, “Olympia” would be installed in Louvre.

After Manet’s unsuccessful attempt in 1865, he traveled to Spain, during which time he painted “The Spanish Singer.” In 1866, he met and befriended the novelist Emile Zola, who in 1867 wrote a glowing article about Manet in the French paper Figaro. He pointed out how almost all significant artists start by offending the current public’s sensibilities. This review impressed the art critic Louis-Edmond Duranty, who began to support him as well. Painters like Cezanne, Gauguin, Degas and Monet became his friends.

Some of Manet’s best-loved works are his cafe scenes. His completed paintings were often based on small sketches he made while out socializing. These works, including “At the Cafe,” “The Beer Drinkers” and “The Cafe Concert,” among others, depict 19th-century Paris. Unlike conventional painters of his time, he strove to illuminate the rituals of both common and bourgeoisie French people. His subjects are reading, waiting for friends, drinking and working. In stark contrast to his cafe scenes, Manet also painted the tragedies and triumphs of war. In 1870, he served as a soldier during the Franco-German War and observed the destruction of Paris. His studio was partially destroyed during the siege of Paris, but to his delight, an art dealer named Paul Durand-Ruel bought everything he could salvage from the wreckage for 50,000 francs.

Late Career and Death

In 1874, Manet was invited to show at the very first exhibit put on by impressionist artists. However supportive he was of the general movement, he turned them down, as well as seven other invitations. He felt it was necessary to remain devoted to the salon and its place in the art world. Like many of his paintings, Edouard Manet was a contradiction, both bourgeoisie and common, conventional and radical. A year after the first impressionist exhibit, he was offered the opportunity to draw illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe’s book-length French edition of “The Raven.” In 1881, the French government awarded him the Légion d’honneur.

He died two years later in Paris, on April 30, 1883. Besides 420 paintings, he left behind a reputation that would forever define him as a bold and influential artist.