No products in the cart.

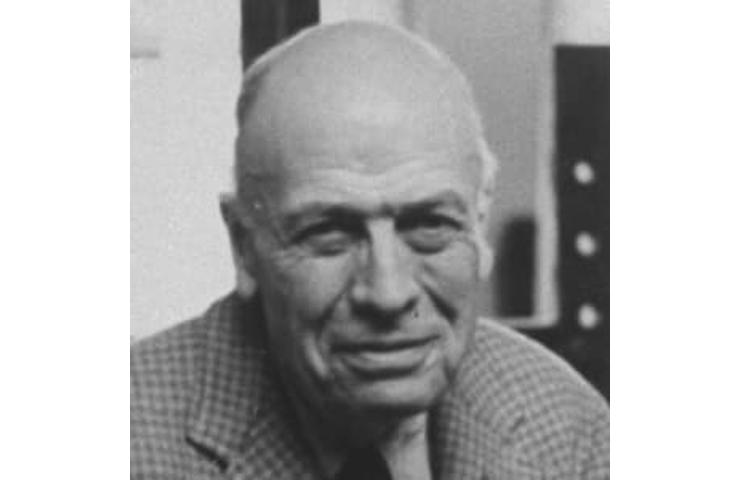

Painter, Artist (1882–1967)

Artist Edward Hopper was the painter behind the iconic late-night diner scene Nighthawks (1942), among other celebrated works.

Synopsis

Born in 1882, Edward Hopper trained as an illustrator and devoted much of his early career to advertising and etchings. Influenced by the Ashcan School and taking up residence in New York City, Hopper began to paint the commonplaces of urban life with still, anonymous figures, and compositions that evoke a sense of loneliness. His famous works include House by the Railroad (1925), Automat (1927) and the iconic Nighthawks (1942). Hopper died in 1967.

Early Life by the Hudson

Edward Hopper was born on July 22, 1882, in Nyack, New York, a small shipbuilding community on the Hudson River. The younger of two children in an educated middle-class family, Hopper was encouraged in his intellectual and artistic pursuits and by the age of 5 was already exhibiting a natural talent. He continued to develop his abilities during grammar school and high school, working in a range of media and forming an early love for impressionism and pastoral subject matter. Among his earliest signed works is an 1895 oil painting of a rowboat. Before deciding to pursue his future in fine art, Hopper imagined a career as a nautical architect.

After graduating in 1899, Hopper briefly participated in a correspondence course in illustration before enrolling at the New York School of Art and Design, where he studied with teachers such as impressionist William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri of the so-called Ashcan School, a movement that stressed realism in both form and content.

Darkness and Light

Having completed his studies, in 1905 Hopper found work as an illustrator for an advertising agency. Although he found the work creatively stifling and unfulfilling, it would be the primary means by which he would support himself while continuing to create his own art. He was also able to make several trips abroad—to Paris in 1906, 1909 and 1910 as well as Spain in 1910—experiences that proved pivotal in the shaping of his personal style. Despite the rising popularity of such abstract movements as cubism and fauvism in Europe, Hopper was most taken by the works of the impressionists, particularly those of Claude Monet and Edouard Manet, whose use of light would have a lasting influence on Hopper’s art. Some works from this period include his Bridge in Paris (1906), Louvre and Boat Landing (1907) and Summer Interior (1909).

Back in the United States, Hopper returned to his illustration career but also began to exhibit his own art as well. He was part of the Exhibition of Independent Artists in 1910 and the international Armory Show of 1913, during which he sold his first painting, Sailing (1911), displayed alongside works by Paul Gaugin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas and many others. That same year, Hopper moved to an apartment on Washington Square in New York City’s Greenwich Village, where he would live and work for most of his life.

Wife and Muse

Around this time, the statuesque Hopper (he stood 6’5″) began making regular summer trips to New England, whose picturesque landscapes provided ample subject matter for his impressionist-influenced paintings. Examples of this include Squam Light (1912) and Road in Maine (1914). But despite a flourishing career as an illustrator, during the 1910s Hopper struggled to find any real interest in his own art. However, with the arrival of the new decade came a reversal of fortune. In 1920, at age 37, Hopper was given his first one-man show, held at the Whitney Studio Club and arranged by art collector and patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. The collection primarily featured Hopper’s paintings of Paris.

Three years later, while summering in Massachusetts, Hopper became reacquainted with Josephine Nivison, a former classmate of his who was herself a fairly successful painter. The two were married in 1924 and quickly became inseparable, often working together and influencing each other’s styles. Josephine also jealously insisted that she be the sole model for any future paintings featuring women and so inhabits much of Hopper’s work from that time forward.

(Later information from Josephine’s diaries presented by art scholar Gail Levin in the 1995 book Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography presented the marriage as becoming highly dysfunctional and marked by abuse from Hopper, though another couple who knew the two challenged such claims.)

Josephine was instrumental in Hopper’s transition from oils to watercolors and shared her art-world connections with him. These connections soon led to a one-man exhibition for Hopper at the Rehn Gallery, during which all of his watercolors were sold. The success of the show allowed Hopper to quit his illustration work for good and marked the beginning of a lifelong association between Hopper and the Rehn.

Sought After Art and ‘Nighthawks’

At last able to support himself with his art, during the second half of his life Hopper produced his greatest, most lasting work, painting side by side with Josephine at their Washington Square studio or on one of their frequent trips to New England or abroad. His work from this period frequently indicates their location, whether it is the quiet image of the lighthouse at Cape Elizabeth, Maine, in his The Lighthouse at Two Lights (1929) or the lonely woman sitting in his New York City Automat (1927), which he first exhibited at his second show at the Rehn. He sold so many paintings at the show that he was unable to exhibit for some time afterward until he had produced enough new work.

Another notable work from this era is his 1925 painting of a Victorian mansion beside a railroad track titled House by the Railroad, which in 1930 was the first painting acquired by the newly formed Museum of Modern Art in New York. Further indicating the esteem in which the museum held Hopper’s work, he was given a one-man retrospective there three years later.

But despite this overwhelming success, some of Hopper’s finest work was still to come. In 1939 he completed New York Movie, which pictures a young female usher standing alone in a theater lobby, lost in thought. In January 1942 he completed what is his best-known painting, Nighthawks, featuring three patrons and a waiter sitting inside a brightly lit diner on a quiet, empty street. With its stark composition, masterful use of light and mysterious narrative quality, Nighthawks arguably stands as Hopper’s most representative work. It was purchased almost immediately by the Art Institute of Chicago, where it remains on display to the present day.

Accolades in Later Years

With the rise of abstract expressionism near the middle of the 20th century, Hopper’s popularity waned. In spite of this, he continued to create quality work and receive critical acclaim. In 1950 he was honored with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and in 1952 he was chosen to represent the United States in the Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition. Several years later he was the subject of a Time magazine cover story, and in 1961 Jacqueline Kennedy chose his work House of Squam Light, Cape Ann to be displayed in the White House.

Although his gradually failing health slowed Hopper’s productivity during this time, works such as Hotel Window (1955), New York Office (1963) and Sun in an Empty Room (1963) all display his characteristic themes, moods and ability to convey stillness. He died on May 15, 1967, at his Washington Square home in New York City at the age of 84, and was buried in his hometown of Nyack. Josephine died less than a year later and bequeathed both his work and hers to the Whitney Museum.