No products in the cart.

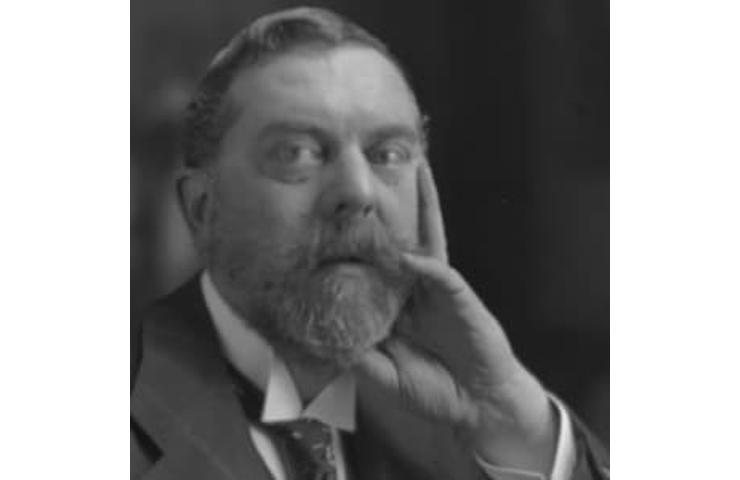

Painter (1856–1925)

John Singer Sargent was an Italian-born American painter whose portraits of the wealthy and privileged provide an enduring image of Edwardian-age society.

Synopsis

John Singer Sargent was born in 1856 in Florence, Italy. He earned early acclaim for his promise as a portraitist, although he drew harsh reviews for his exhibition of Madame X at the Paris Salon of 1884. He reclaimed a favorable reputation by the end of the decade, and by the early 20th century he was devoting more time to war-themed paintings, landscapes and watercolors. Sargent died in 1925 in London, England.

Background and Early Years

Artist. John Singer Sargent was born January 12, 1856, to American parents living in Florence, Italy. Although he spent most of his life in Europe, both of his parents were raised in the United States and the artist considered himself to be an American. His father, Fitzwilliam Sargent, was a physician who came from an early colonial family and grew up in Philadelphia. His mother, Mary Newbold Singer, married Fitzwilliam Sargent in 1850. While the couple was enamored of Europe, they initially arrived there due to tragic circumstances, taking a tour as a means of escape following the tragic death of their first child. The Sargents had originally intended to return to the United States, but instead became expatriates.

John Singer Sargent began demonstrating his artistic talents at a young age, and soon took up the study of painting in a formal setting. His first known enrollment in art classes took place in Florence at the Accademia delle Belle Arti, in his late teens. During the winter of 1873-74, Sargent honed his skills, convincing his father that it was well worth encouraging his artistic pursuits. Father and son traveled together to Paris in the spring of 1874 so that John Singer Sargent could continue his studies in the art capital of Europe.

Parisian Development

While in Paris, Sargent studied under a relatively young teacher named Carolus-Duran, who was teaching his students to break free of the rigidity of the old masters’ style. Carolus-Duran’s method emphasized skipping the step of making detailed sketches and heading straight to the canvas with a paintbrush. Sargent internalized these techniques; his later works would come to be recognized for their immediacy, emotional depth and refined technique.

In May 1876, when Sargent was in his early 20s, he made his first trip to the United States, accompanied by his mother and sister, Emily. The family visited Philadelphia and Niagara Falls, among other places. Much like his mother, Sargent found that he was intensely drawn to travel. When he got back to Europe, he continued traveling, using his voyages as opportunities to study great works of art and try his hand at portraying diverse locations. In Spain, Sargent admired and copied the works of Diego Velásquez; in Venice, he cultivated an appreciation for its picturesque canals, to which he would return many times. Travel scenes would form a major element of his work.

Back in Paris, Sargent submitted a portrait of his teacher, Carolus-Duran, to the Salon of 1879. It won him an honorable mention, and his reputation as a portraitist was given a boost. Between the years of 1877 and 1882, Sargent submitted many types of paintings to the Salon, though his portraits generally won the most positive attention.

‘Madame X’ Scandal and Fallout

Sargent’s reputation took a turn for the worse with the exhibition of Madame X at the Salon of 1884. Because it defied many of the accepted standards of the day, and was slightly risqué in its portrayal of a woman in a low-cut, nearly sleeveless dress, it turned many of his admirers against him. The mother of the woman who had sat for the portrait, Madame Gautreau (who was actually American), even asked Sargent to remove it. Today, Madame X is considered one of his most celebrated works.

Rather than stay in a city in which public opinion had turned against him, Sargent left Paris and began spending much of his time in England, making it his permanent home in 1886. The country he had adopted had not quite adopted him, though; the English were reluctant to sit for Sargent’s portraits because of the scandal of Madame X. Not wanting their own portraits to turn out the same way, they refrained from giving him commissions.

Public Recognition

Sargent was not discouraged. On a pair of trips to the United States in 1887 and 1890, he found that Americans were not averse to being painted by him, and many members of American high society sat for his portraits. He often painted his subjects as if they were caught in the middle of motion, with faces both highly individualized and expressive.

The turning point for Sargent’s career in England came when he showed his Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (painted 1885-86) at the London Royal Academy. The piece, undeniably one of Sargent’s masterpieces, incorporated Victorian themes and a calculated impressionist influence that depicted two girls lighting lanterns among flowers in spring. The English recognized the painting’s greatness, and members of the elite were soon lining up to commission their own likenesses.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose was important, too, as an example of the impact that Impressionism had made on Sargent’s style. He had become acquainted with and learned from both Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, masters of the movement. Sargent, like Monet, was particularly fascinated with light, and became highly skilled at portraying it. However, in contrast to the French painters’ work, Sargent’s paintings remained fairly literal, retaining crisp forms and not dissolving entirely into streaks of color.

Later Years and Styles

Although his portraits were highly praised, Sargent eventually grew tired of painting them — they took up a large amount of his time, and there seemed to be no end to his new commissions. Sargent backed away from the portrait business between 1907 and 1910 to leave himself time to focus on other projects, in particular a set of murals for the Boston Public Library. He also increasingly turned his attention to watercolors around this time, forging a strong reputation for his work in that medium.

The coming of World War I changed Sargent’s subject matter, for a time. Visiting the Western Front at the request of the British government, which had asked him to paint a scene commemorating the war, Sargent created Gassed, an appropriately dark work, which depicted soldiers enduring the deplorable conditions that marked life in the Great War.

Sargent was also commissioned to create murals in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. His creations span the museum’s grand staircase and rotunda. Additionally, more of his works can be seen at Harvard University’s Widener Library — a tribute to those who died in World War I.

Sargent passed away in his sleep on April 14, 1925, at the age of 69. He left behind a large body of work, including portraits, travel scenes, watercolors and impressionistic masterpieces that have defined his reputation into the current century; his works are still exhibited around the world. Although the artist and his portrait sitters are all gone, his admirable skill has given future generations a glimpse into the lives and characters of people long gone — certainly a gift to future generations, and one that those future generations have so far recognized as precious.