No products in the cart.

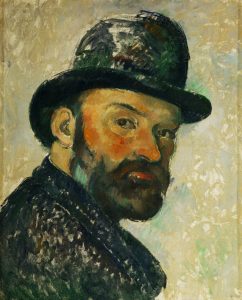

Painter (1839–1906)

Post-Impressionist French painter Paul Cézanne is best known for his incredibly varied painting style, which greatly influenced 20th century abstract art.

Synopsis

The work of Post-Impressionist French painter Paul Cézanne, born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839, can be said to have formed the bridge between late 19th century Impressionism and the early 20th century’s new line of artistic inquiry, Cubism. The mastery of design, tone, composition and color that spans his life’s work is highly characteristic and now recognizable around the world. Both Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso were greatly influenced by Cézanne.

Early Life

Famed painter Paul Cézanne was born on January 19, 1839, in Aix-en-Provence (also known as Aix), France. His father, Philippe Auguste, was the co-founder of a banking firm that prospered throughout the artist’s life, affording him financial security that was unavailable to most of his contemporaries and eventually resulting in a large inheritance. In 1852, Paul Cézanne entered the Collège Bourbon, where he met and befriended Émile Zola. This friendship was decisive for both men: with youthful romanticism, they envisioned successful careers in Paris’ booming art industry—Cézanne as a painter and Zola as a writer.

Consequently, Cézanne began to study painting and drawing at the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Design) in Aix in 1856. His father opposed the pursuit of an artistic career, and in 1858 he persuaded Cézanne to enter law school at the University of Aix-en-Provence. Though Cézanne continued his law studies for several years, he was simultaneously enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he remained until 1861.

In 1861, Cézanne finally convinced his father to allow him to go to Paris, where he planned to join Zola and enroll at the Académie des Beaux-Arts (now the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris). His application to the academy was rejected, however, so he began his artistic studies at the Académie Suisse instead. Though Cézanne had gained inspiration from visits to the Louvre—particularly from studying Diego Velázquez and Caravaggio—he found himself crippled by self-doubt after five months in Paris. Returning to Aix, he entered his father’s banking house, but continued to study at the School of Design.

The remainder of the decade was a period of flux and uncertainty for Paul Cézanne. His attempt to work in his father’s business was abortive, so in 1862 he returned to Paris, where he stayed for the next year and a half. During this period, Cézanne met Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro and became acquainted with the revolutionary work of Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet. The budding artist also admired the fiery romanticism of Eugène Delacroix’s paintings. But Cézanne, never entirely comfortable with Parisian life, periodically returned to Aix, where he could work in relative isolation. He retreated there, for instance, during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871).

Works of the 1860s

Paul Cézanne’s paintings from the 1860s are peculiar, bearing little overt resemblance to the artist’s mature and more important style. The subject matter is brooding and melancholy and includes fantasies, dreams, religious images and a general preoccupation with the macabre. His technique in these early paintings is similarly romantic, often impassioned. For his “Man in a Blue Cap” (also called “Uncle Dominique,” 1865-1866), he applied pigments with a palette knife, creating a surface everywhere dense with impasto. The same qualities characterize Cézanne’s unique “Washing of a Corpse” (1867-1869), which seems to both portray events in a morgue and be a pietà—a representation of the biblical Virgin Mary.

A fascinating aspect of Cézanne’s style in the 1860s is the sense of energy in his work. Though these early works seem groping and uncertain in comparison to the artist’s later expressions, they nevertheless reveal a profound depth of feeling. Each painting seems ready to explode beyond its limits and surface. Moreover, each seems to be the conception of an artist who could either be a madman or a genius—the world will likely never know, as Cézanne’s true character was unknown to many, if not all, of his contemporaries.

Though Cézanne received encouragement from Pissarro and some of the other Impressionists during the 1860s and enjoyed the occasional critical backing of his friend Zola, his pictures were consistently rejected by the annual Salons and frequently inspired more ridicule than did the early efforts of other experimenters in the same generation.

Cézanne and Impressionism

In 1872, Cézanne moved to Pontoise, France, where he spent two years working very closely with Pissarro. Also during this period, Cézanne became convinced that one must paint directly from nature. One result of this change in artistic philosophy was that romantic and religious subjects began to disappear from Cézanne’s canvases. Additionally, the somber, murky range of his palette began to give way to fresher, more vibrant colors.

A direct result of his stay in Pontoise, Cézanne decided to participate in the first exhibition of the “Société Anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc.” in 1874. This historic exhibition, which was organized by radical artists who’d been persistently rejected by the official Salons, inspired the term “Impressionism”—originally a derogatory expression coined by a newspaper critic—marking the start of the now-iconic 19th century artistic movement. The exhibit would be the first of eight similar shows between 1874 and 1886. After 1874, however, Cézanne exhibited in only one other Impressionist show—the third, held in 1877—to which he submitted 16 paintings.

After 1877, Cézanne gradually withdrew from his Impressionist colleagues and worked in increasing isolation at his home in southern France. Scholars have linked this withdrawal to two factors: 1) The more personal direction his work began to take was not well-aligned with that of other Impressionists, and 2) his art continued to generate disappointing responses from the public at large. In fact, after the third Impressionist show, Cézanne did not exhibit publicly for nearly 20 years.

Cézanne’s paintings from the 1870s are a testament to the influence that the Impressionist movement had on the artist. In “House of the Hanged Man” (1873-1874) and “Portrait of Victor Choque” (1875-1877), he painted directly from the subject and employed short, loaded brushstrokes—characteristic of the Impressionist style as well as the works of Monet, Renoir and Pissarro. But unlike the way the movement’s originators interpreted the Impressionist style, Cézanne’s Impressionism never took on a delicate asthetic or sensuous feel; his Impressionism has been deemeed strained and discomforting, as if he were fiercely trying to coalesce color, brushstroke, surface and volume into a more tautly unified entity. For instance, Cézanne created the surface of “Portrait of Victor Choque” through an obvious struggle, giving each brushstroke parity with its adjacent strokes, thereby calling attention to the unity and flatness of the canvas ground, and presenting a convincing impression of the volume and substantiality of the object.

Mature Impressionism tended to forsake the Cézanne’s and other deviating interpretations of the classic style. The artist spent most of the 1880s developing a pictorial “language” that would reconcile both the original and progressive forms of the style—for which there was no precedent.

Mature Work

During the 1880s, Cézanne saw less and less of his friends, and several personal events affected him deeply. He married Hortense Fiquet, a model with whom he’d been living for 17 years, in 1886, and his father died that same year. Probably the most significant event of this year, however, was the publication of the novel L’Oeuvre by Cézanne’s friend Zola. The hero of the story is a painter (generally acknowledged to be a composite of Cézanne and Manet) who is presented as an artistic failure. Cézanne took this presentation as a critical denunciation of his own career, which hurt him deeply, and he never spoke to Zola again.

Cézanne’s isolation in Aix began to lessen during the 1890s. In 1895, largely due to the urging of Pissarro, Monet and Renoir, art dealer Ambroise Vollard showed several of Cézanne’s paintings. As a result, public interest in Cézanne’s work slowly began to develop. The artist sent pictures to the annual Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1899, 1901 and 1902, and he was given an entire room at the Salon d’Automne in 1904.

While painting outdoors in the fall of 1906, Cézanne was overtaken by a storm and became ill. The artist died in the city of his birth, Aix, on October 22, 1906. At the Salon d’Automne of 1907, Cézanne’s artistic achievements were honored with a large retrospective exhibition.

Artistic Legacy

Cézanne’s paintings from the last three decades of his life established new paradigms for the development of modern art. Working slowly and patiently, the painter transformed the restless power of his earlier years into the structuring of a pictorial language that would go on to impact nearly every radical phase of 20th century art.

This new language is apparent in many of Cézanne’s works, including “Bay of Marseilles from L’Estaque” (1883-1885); “Mont Sainte-Victoire” (1885-1887); “The Cardplayers” (1890-1892); “Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup” (1866); and “The Large Bathers” (1895-1905). Each of these works seems to confront the viewer with its identity as a work of art; landscapes, still lifes and portraits seem to spread out in all directions across the surface of the canvas, demanding the viewer’s full attention.

Cézanne used short, hatched brushstrokes to help ensure surface unity in his work as well as to model individual masses and spaces as if they themselves were carved out of paint. These brushstrokes have been credited with employing 20th century Cubism’s analysis of form. Furthermore, Cézanne simultaneously achieved flatness and spatiality through his use of color, as color, while unifying and establishing surface, also tends to affect interpretations of space and volume; by calling primary attention to a painting’s flatness, the artist was able to abstract space and volume—which are subject to their medium (the material used to create the work)—for the viewer. This characteristic of Cézanne’s work is viewed as a pivotal step leading up to the abstract art of the 20th century.